A collection of oral histories offers a penetrating look at life in the Israeli-occupied West Bank and Gaza Strip.

Gaza could be uninhabitable by 2020. More than 2,000 Palestinians were killed in 2014 and more than 17,000 were injured. Israel arrests and detains between 500 and 700 Palestinian children every year. In August of 2015 alone, Israeli forces demolished nearly 150 Palestinian structures.

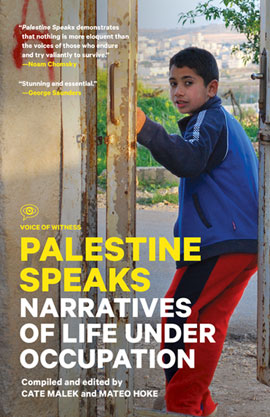

When it comes to the Israeli occupation of the Gaza Strip and the West Bank, there’s no shortage of statistics. But while numbers may tell, it’s the stories that show the deep impact the occupation makes on Palestinians’ lives. Enter Palestine Speaks: Narratives of Life under Occupation, a moving collection of interviews compiled and edited by Cate Malek and Mateo Hoke and published by Voice of Witness in the U.S. and Verso in the U.K..

When it comes to the Israeli occupation of the Gaza Strip and the West Bank, there’s no shortage of statistics. But while numbers may tell, it’s the stories that show the deep impact the occupation makes on Palestinians’ lives. Enter Palestine Speaks: Narratives of Life under Occupation, a moving collection of interviews compiled and edited by Cate Malek and Mateo Hoke and published by Voice of Witness in the U.S. and Verso in the U.K..

The detailed oral histories offer the reader more than a look at life under Israeli military rule. By including voices from a wide range of backgrounds, they also offer an intimate look at Palestinian society itself: from a lawyer from Dheisheh refugee camp who spent nearly 20 years in Israeli prisons to a young female journalist in Gaza to a West Bank farmer to a middle-aged housewife. Too often the media represents Palestinians as a monolithic group, relying on convenient stereotypes like the humble villager or the freedom fighter with an indomitable spirit, the martyr hero. Palestine Speaks breaks such Orientalist depictions by bringing us individuals rather than a faceless, fetishized mass.

The reader also gets a glimpse of history through Palestinian eyes. Recalling the Six Day War, Ghassan Andoni, a founder of the International Solidarity Movement, says:

I saw the soldiers coming into Beit Sahour with their weapons. Everybody was scared. Some people were saying the Israelis would kill us, we should leave, and others were saying we shold stay. But it was over in a week. I still remember an injured bird that had been trapped in my relatives’ house after the bombing ended. I caught it and cared for it while I was waiting to go home. After a couple of weeks, the Red Cross arranged a bus ride for me and others back to Jordan. I tried to take the bird with me back home. I held it in my hands on the trip back, but it died on the way.

The editors could have ended the passage at “But it was over in a week”—indeed, those who are focused more on the story of the conflict rather than the stories of the people who live the conflict would have stopped there. Instead, Malek and Hoke give the narrators room to express themselves fully; the inclusion of details like Andoni’s attempt to rescue the bird bring nuance and complexity to the stories, helping readers better see and understand the people behind the statistics—their desires, hopes, fears. Their struggles. Their heartbreaks. This collection is revelatory for those who have neither the resources to travel to the occupied Palestinian Territories nor access to the people who live there.

Each chapter is compelling but, in addition to Andoni’s narrative, I was particularly taken with two stories—that of Muhanned al Azzah, an artist from Al Azzah refugee camp who joined the PFLP when he was a teenager, and Nader al Masri, a runner in Gaza. Both offer viewpoints rarely heard in the current discussion about the conflict and Palestinian society. While much has been written about administrative detention—perhaps because it’s a relatively straightforward example of injustice—the media rarely addresses stories of political repression like al Azzah’s, who was imprisoned because of his PFLP membership. Al Azzah’s story offers a look at how jailing one son puts the whole family behind psychological bars; he also speaks about the lasting impact of his imprisonment. Further, the image of a rising artist who exhibits in London might upend some readers’ ideas about the PFLP and who is attracted to the party.

Al Masri’s story speaks of a man who quietly defies multiple layers of oppression—the Israeli occupation and blockade as well as the expectations of Palestinian society. The feeling of freedom al Masri has while running points to the limits that Israel puts on Palestinian life. That he persists—“When I was young, before I had a family, I’d even run when there was an Israeli invasion or bombing in Gaza City,” al Masri says—also reminds that there are many means of resistance, including the simple act of focusing on and following one’s dreams.

Of the 16 oral histories in the book, two belong to Israelis—one a settler, the other a radical leftist who lives in Ramallah. In the introduction, the editors explain the decision to include these Israeli voices: “We share their stories partly because Israeli citizens living in the West Bank make up a substantial portion—perhaps as much as 10 percent—of the total population of Palestine. And because many of our narrators often refer to settlers throughout this book, we felt it journalistically responsible to include Amiad’s narrative in order to offer readers a look at life within a settlement…”

There’s still something vaguely uncomfortable about seeing Israeli stories behind a cover that reads Narratives of Life under Occupation. And it’s worth noting that predecessors to Palestine Speaks, similar books composed of Palestinians’ narratives—namely Arthur Neslen’s In Your Eyes a Sandstorm: Ways of Being Palestinian and Wendy Pearlman’s Occupied Voices—did not include Israelis.

However, I could argue against myself and say that the discomfort I felt about their inclusion is representative of life in the West Bank. One can’t move without seeing the settlements and the Jewish Israelis who live in them—their presence is inescapable.

I also felt unsure about the editors’ decision to focus on Palestinian voices from the West Bank and Gaza only. I could imagine the criticism this choice might draw: the editors might be accused of failing to acknowledge the Palestinian claim to all of historic Palestine, an area some consider every bit as occupied as the West Bank and Gaza. Some might also take issue with the absence of narratives from the Palestinian diaspora.

But Malek and Hoke were damned if they do and damned if they don’t, as is often the case when discussing Israel/Palestine. Had they included Palestinian citizens of Israel in the book, they ran the risk of drawing the ire of the pro-Israel right who would have taken issue with the title Palestine Speaks, asking if the editors (and, by extension, the publisher) consider UN and internationally recognized Israel to be Palestine.

And my quibbles are small. Palestine Speaks is an indispensable text. By presenting the personal stories of Palestinians, this book complicates what the media often depicts as a black and white, bilateral conflict between equals. The narratives presented in Palestine Speaks also remind that those who live under occupation want something breathtakingly simple: freedom and human rights.

Full disclosure: Editor Cate Malek is both a friend and colleague; my name is listed in the acknowledgments.