Malcolm X’s descriptions of the black experience in the United States helped me understand that Amir’s death was not ‘normal,’ but rather a result of Israel’s policies toward its Palestinian minority.

I lost my best friend on the night between June 28-29th, 2000. Amir Qadri (Arafat) was killed by a stray bullet shot by armed men who came into his neighborhood in the city of Lyd (“Lod” in Hebrew) and began firing. He was only 15 when he died. The gunfire was a result of a conflict between the shooters and Amir’s neighbors. Amir was sitting on the balcony of his other neighbors’ home, watching television and eating sunflower seeds as he was preparing for the big semifinal match between France (with our favorite player, Zidane) and Portugal in the UEFA European Championship.

That same day we came back from the gym. We parted ways at 7:30 p.m. after Amir tried to convince me to come watch the game at his place. “We’ll sit outside, it won’t be too hot today. Don’t be a jerk,” he said. He even promised that we’ll be able to sneak a few puffs from the nargileh. “Forget it, I’ll watch the game at home. I’m tired of you, I’ve been around you all day,” I responded as we stood outside his house. “You jerk,” he responded, and turned to walk inside. These were the last words we ever exchanged.

The period following Amir’s death was the most difficult of my life. I only understood the significance of what had happened several months later, as the walls of denial came down, only to be replaced by a deep, painful sorrow.

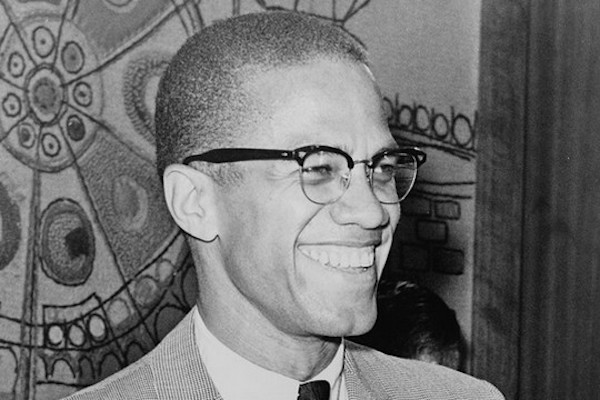

It was around then that I first encountered Malcolm X. I learned his life story in reverse chronological order, from his assassination to his joining the Nation of Islam under Elijah Muhammad. I couldn’t get his biography story out of my head; twenty years before I was born, people close to Malcolm – from his own community – shot him, despite the fact that both the FBI and the CIA knew about the plan to assassinate him. My best friend, who was like a brother to me, was killed by members of his own community, and like in Malcolm’s case, the authorities knew that Amir’s killers were in Lyd and never acted. In Amir’s case, those responsible for the murder (like those who were “really” responsible for Malcolm’s murder), were never put on trial.

‘A martyr of racism’

I began to listen to recordings of Malcolm’s speeches. At first it was his booming voice that provided an outlet to vent my anger. As I got older I began reading his writings and listening to his interviews, which helped shape my political-social identity. His descriptions of the black community in the United States during the 50s and 60s helped ease my pain; I was able to tell myself that what happened to Amir was not new — that the authorities always cooperate and support violence among oppressed minorities, which inevitably lead to the death of their leaders. Only then did I understand Amir’s aunt when she called her nephew a “shaheed of racism” during her eulogy.

I spent the following summer in the United States, where I became aware of the similarities between the black struggle for equality, which is ongoing, and our struggle as a Palestinian minority for equality. For me, Malcolm represented something beyond a brave black leader who wasn’t afraid of the white establishment — he was a daring leader who supported equality around the world. For all people.

His opponents described him as a racist who supported full separation, a claim that always astounded me. I never understood how they could trash a man who gave so much back to his community, who shook young black people and freed them of the white consciousness that taught them they were nothing. He taught them that they need to get an education, because only that will give them the tools to free themselves. “Not just carpenters, but lawyers,” he said. “Not just construction workers, but doctors,” I would say to anyone who showed the slightest interest.

In 1964, Malcolm returned from his Hajj to Mecca, where he circled the Kaaba with “blue-eyed, yellow and black” Muslims, with new insights on how to lead the black resistance. It was there, where he felt true equal for the first time in his life, that he understood the true meaning of Islam and decided to renounce the idea of separation. Malcolm tried to connect the true principles of Islam to the politicization of his struggle — an act that directly threatened the political establishment, which viewed Malcolm as a representative of “black violence.” This was the same political establishment that refused to lift a finger against the violence of Elijah Muhammad, who at that point had become Malcolm’s rival and was actively threatening his life. The story of Malcolm X’s death encompasses the establishment’s fear of the oppressed, one that has understood that only violence will be able to do away with ideas of liberation.

Arab Israeli X

Since Saturday was our 50th year without Malcolm, I decided to share a video of an interview that encompasses the similarities between the oppression of blacks in America and Palestinians in Israel. It is a classic example of how which Malcolm’s ideas are relevant for oppressed minorities across the world:

The video shows Malcolm being interviewed by three racists who continue to ask him about his “real” last name. “My father got his last name from his grandfather, and his grandfather, and his grandfather got it from his grandfather, who got it from the slave-master,” he tells them. Likewise, the Arabs in Israel were given the name “Arab Israelis” by the colonial Zionist establishment in order to cover up our national, historical identity.

The term “Arab Israelis” not only distorts our history, it is also offensive and hurtful. It is a term that is meant to separate us from the larger Arab world, and erase us from the Palestinian story. Malcolm X teaches us to resist any attachment to the oppressors’ narrative, which prevents us from freeing our minds. For us, Palestinians, it is important to resist any relation between us and our occupiers. They will never be able to change our last name, so they tried to include us in their new nation. We cannot allow this to happen.

And Amir? Amir won’t be a lawyer or a doctor like our mothers predicted, or like Malcolm would have wanted. He won’t be a Palestinian or an Israeli, but rather a personal memory of all those who knew him. “I’m tired of you, I’ve been around you all day.” It’s a sentence I refuse to forget, one that will stay with me as long as I live — and I’m glad.

This article was first published Local Call. Read it in Hebrew here.

Related:

Why are Palestinian citizens expected to be loyal to Israel?

Israel’s other war: Silencing Palestinian citizens