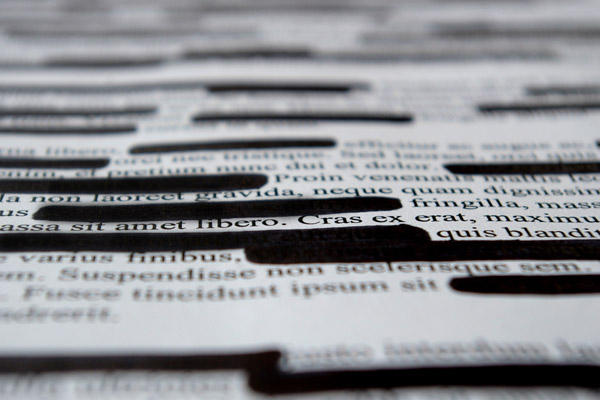

From military censorship to the government deciding who is and isn’t a journalist, Israeli authorities use various tools to interfere with the press. An important disclosure to our readers.

When +972 Magazine was formed by a group of journalists and bloggers over five years ago, its founders decided that the site would not have an editorial line or political agenda save for three common denominators to which everyone was willing to commit: human rights, opposing the occupation, and freedom of information.

The first two values are likely evident to almost anyone who stumbles across +972 Magazine, and certainly to regular readers. The third value manifests itself primarily behind the scenes, although in its essence is journalism itself.

Late last month, a Facebook account belonging to Chief IDF Censor Col. Ariella Ben Avraham sent a message to +972 Magazine and dozens of new media news sites, blogs and Facebook accounts detailing “the obligation to submit to the censor [for prior review] items relating to security.”

Col. Ben Avraham, who only recently assumed the role of chief military censor, appears to be expanding her office’s priorities and taking an aggressive new line against new and social media outlets.

Prior to this article, in more than five years of publication +972 had never submitted anything to the IDF Censor, although we have published materials from other sites that were reviewed by the Censor.

After consulting with counsel, we believe that at this point in time we will have no choice but to submit certain articles to the military censor before publication in the future. And although we are forbidden from publishing the full list of topics that are subject to censorship, they include everything from equipment the army is using in the West Bank, troop movements, the location of rocket strikes, the identities of high-ranking security officials, and certain information about national infrastructure.

If and when the IDF Censor does demand changes to one of our articles we will be forbidden from telling you, our readers, when and where we were censored. And while we begrudgingly accept our legal obligation to submit certain articles for prior review, we plan to fight with our full resources any attempts at actually censoring us.

A permanent state of emergency

The Israeli military censor draws its authority from emergency regulations that have been in place for over 70 years, which originated in the British Mandate period.

While other countries have formal mechanisms for requesting that journalists refrain from publishing certain information relating to national security, Israel is all but alone among Western democratic states that have a legally binding state censor. Nowhere else must reported materials be submitted for prior review.

Yet censorship is simply the way things have always been done in Israel – a state of affairs that remained effective and possible as long as there was a limited number of newspapers and broadcasters that needed to be censored.

As the dawn of the Internet age lowered the entry barriers into journalism and the mass distribution of information, however, the practice of state censorship has often devolved into the realm of the absurd. Information censored in traditional media outlets is simultaneously accessible on private blogs, on social media, and in overseas news outlets available to anyone with an Internet connection.

One of the most ludicrous cases in recent years was the secret arrest of whistleblower Anat Kamm, which was an open secret for months until journalists, bloggers and regular citizens lost their patience. The ridiculous ease of bypassing the censor (or in this case a gag order — more on that later) eventually became apparent to anyone walking around Tel Aviv, who would have found graffiti on major boulevards reading: “Google ‘Anat Kamm’.” (Details of the affair had already been reported by American blogger Richard Silverstein.)

The previous IDF Censor, who finished her 10-year term at the end of 2015, made no secret of her desire to see the entire apparatus become obsolete in favor of a more voluntary — and civilian — system, which would bring Israel in line with other democratic countries. The new censor’s vision, it appears, is diametrically opposed.

Contacted by +972, the IDF Censor claimed there has been no change in policy and that individual bloggers have submitted content for review in the past. Asked about its criteria for preemptively contacting bloggers and social media accounts to demand compliance, the Censor refused to elaborate. One blogger who was not contacted by the Censor recently decided to try and submit an article anyway. He was told to “not worry about it,” raising questions about who was indeed sent a censorship compliance letter.

Secrets secrets are no fun

Censorship’s most severe threat to democracy is that it limits the press’s ability to act as a watchdog over the government and those who otherwise hold power over our lives. State security agencies, the government and individual politicians often bear interests that can be at odds with the public’s own interest, and an independent press acts as a check on state power.

And yet, states can have legitimate secrets. For that exact reason, codes of journalistic ethics and responsibility dictate that reporters and editors must always weigh the public’s interest to know against the potential harm publication might cause. The problem with prior restraint and state censorship is that it allows the state, and the state alone, to decide what is in the public interest. When that decision-making process is unilateral, the conditions become ripe for the abuse of power, corruption, oppression, and cover-ups of all the above.

Such fears are not unfounded, certainly not in Israel. The most egregious case in which the IDF Censor was complicit in a government cover-up — that we know of — was the Bus 300 Affair, in which security officials used the censor to cover up extrajudicial killings. The Anat Kamm affair, by the way, also centered on exposing extrajudicial killings.

The foreign press

The irony of the censorship regime in Israel is that a lot of censored information gets out sooner or later (see: Prisoner X, Anat Kamm, Bus 300, the Lavon Affair, Israel’s “reported by the foreign press” nuclear weapons program, and on and on).

The vast majority of the Israeli press complies with the IDF Censor but a significant portion of the foreign press does not.

While a number of major international news outlets and wire services do submit security related articles for approval by the IDF Censor, others take what the New York Times has called the “don’t ask/hope they don’t tell approach” of ignoring the legal obligation, although even that isn’t clear cut.

Asked whether it has increased enforcement of the censorship law vis-à-vis the foreign press operating in Israel, a representative of the IDF Censor claimed the foreign press already complies. Asked about those that don’t, she responded that the IDF Censor “can” file complaints with the police, but declined to say whether such a step has been taken in recent years. “We operate in a democratic country and we know the limits of our manpower,” she added.

And while Israel (to the best of our knowledge) has not prosecuted any journalists for violating the censorship law in recent years, the government has other ways of leveraging compliance.

“You can’t work in this country without a Government Press Office card,” Foreign Press Association chairman Luke Baker told +972, “and you can’t get a Government Press Office card without signing an agreement committing to respect the censorship law.”

The government decides who is a journalist

In a number of ways the state is able to influence what information is reported, how it is reported, and who can report it through the Government Press Office (GPO). (Side note: You need a license from the Interior Ministry in order to publish a newspaper in Israel. In the past decade, 62 such applications were rejected.)

Carrying a GPO card gives journalists access to official events, the scenes of newsworthy incidents, is often a condition for cooperation from official spokespeople, and offers protection from arrest while covering protests. In other words, government accreditation makes reporting much safer and more effective. (Foreign journalists must have the GPO’s endorsement in order to even receive a visa to work in Israel.)

But by giving itself the power to decide who is a legitimate journalist, the GPO (which operates as part of the Prime Minister’s Office) also inherently gets to decide who is not a legitimate journalist. And as with any decision made by government bureaucrats subordinate to politicians, such decisions can at times be driven by political considerations.

That has been true in the past and under the current government. It is relatively common for journalists to have to hire lawyers in order to secure and renew their accreditations. Earlier this month Government Press Office director Nitzan Chen said he will considering revoking the press credentials of journalists who pen articles carrying headlines not to his liking.

(+972 Magazine is currently engaged in a years-long battle to be accredited by the GPO as a recognized, and therefore legitimate, news organization.)

But the GPO is not only an office charged with accrediting and liaising with journalists. It is also a political propaganda organ of the Israeli government. According to a December 2014 Knesset report on official hasbara (propaganda) efforts, “The GPO tries to promote the State of Israel’s hasbara in its work with the foreign press,” an effort on which it spent NIS 36.5 million between 2010 and 2014.

One can only imagine the risks of political intervention and conflict of interest when a government body charged with disseminating propaganda is also responsible for accrediting journalists who might happen to be critical of state policy.

Gag orders

Yet another way Israel obstructs freedom of information and an informed body politic is through gag orders.

The IDF Censor might be looking to expand its reach and authority into social and new media, but it has actually become more timid over the years. For the most part the IDF Censor has raised its threshold of what it is willing to censor, largely limiting its intervention to information it believes could pose an “imminent and immediate danger” to state security.

In response, Israeli security agencies — from the civilian police to the Shin Bet to the army to the Mossad — have increasingly asked the courts to step up and act as the guardian of their secrets.

Today, in 2016, journalists and editors receive at least one gag order a week via email, fax and these days, even by WhatsApp. Unlike the military censor, which will generally only censor the most sensitive details or ask to change the specific wording of a report, court gag orders can be sweeping — barring publication of any detail of an affair, and often cover the existence of the gag order itself.

And unlike in dealings with the IDF Censor, there is generally no press representative (representing the public’s interest to know) to argue against the issuance of gag orders.

Self-censorship

But the most problematic way that the state controls information reaching the public is actually the one method through which it exercises the least amount of control: self-censorship.

In a media environment that has never existed without various forms of accepted state intervention and censorship, the press eventually starts censoring itself. And that is the most dangerous place we can reach. We at +972 pledge to be vigilant in not letting self-censorship affect our reporting and writing.

The Palestinian press

And yet, everything mentioned here so far is nothing compared to the magnitude and scope of Israeli restrictions and violations against the Palestinian press — both inside Israel and the occupied territories.

Late last year, authorities shut down a number of Arabic-language newspapers and publications in Israel associated with the Islamic Movement. Other publications are subject to close scrutiny by intelligence and security forces.

In the Occupied Territories, the Israeli military regularly shuts down Palestinian media outlets, and destroys and confiscates journalistic and broadcast equipment. Journalists report being targeted with violence by the military.

Israeli bloggers might have to submit Facebook statuses for censorship but Palestinian journalists are being arrested for posting on social media. Palestinian reporter Muhammad al-Qiq is currently near death due to a lengthy hunger strike against his administrative detention — a practice Israel uses to imprison Palestinians without charge or trial.

Israel also severely restricts the movement of Palestinian journalists. Whereas a GPO card allows Israeli journalists to move through military checkpoints freely, even entering areas of the West Bank where most Jewish Israelis are forbidden from stepping foot, the GPO long ago stopped issuing press cards to Palestinian journalists.

Palestinian journalists do not have the same freedom of movement that their Israeli counterparts have, and reporters of Arab descent have regularly reported being humiliated with discriminatory strip searches and delays at official events to which they have been invited.

Israel ranked 101st in Reporters Without Borders’ Press World Freedom Index last year, largely due to its repression of press freedom among Palestinians.

And that is without even mentioning the far-worse treatment Palestinian journalists face at the hands of the Palestinian Authority and Hamas.

This article was also published in Hebrew on Local Call. Read it here.