Five years after they toppled the tyrants of the Arab world, the youth of the revolutions find themselves caught between the hammer of unemployment and the anvil of ISIS.

By Houda Mzioudet

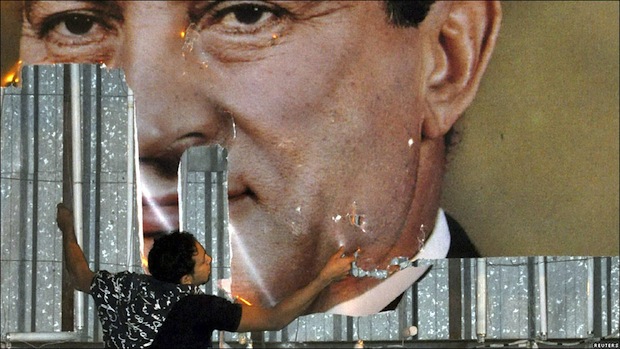

TUNIS — When Mohamed Bouazizi immolated himself in the Tunisian city of Sidi Bouzid on December 17, 2010, few thought it would spark what would later become the Arab Spring. Five years on, with civil wars raging in Syria, Yemen, and Libya, and the so-called Islamic State positing itself as the alternative to democracy, the region has witnessed radical changes.

In late January of this year, Ridha Yahyaoui, an unemployed 28-year-old Tunisian college graduate from the town of Kasserine climbed an electric pole and was electrocuted after he found out that his name had been removed from the list of people promised a government job by the local authorities. His death sparked nationwide protests that reached the capital, Tunis. The message has not changed since 2011: unfulfilled promises of better job opportunities coupled with the stifled hopes of a desperate generation of young people in marginalized areas have added to the grievances of a population that continues to be ignored by the country’s political elite.

Young Tunisians’ disaffection with successive post-revolution governments has paved the way for an uncertain future, with many choosing to join the ranks of radical groups such as ISIS or al-Qaeda affiliated terrorist groups. According to a UN report published in 2015, as many as 5,000 Tunisians have joined ISIS in Syria, Iraq, Libya, Mali, Yemen, and Somalia.

Young Tunisians and Egyptians, whose revolutions inspired other youth movements in the region and elsewhere, were the new face of a generation of millennials — between the disaffected and depoliticized on the one hand and the energetic and hopeful on the other.

It is no wonder, then, that the Spanish leftist political party, Podemos, was inspired by the popular uprisings in both Egypt and Tunisia, and even surpassed the youth movements that toppled Ben Ali, Mubarak, Qaddafi, and Ali Saleh to become the one of the largest political entities in Spain. Podemos, founded in 2014, succeeded at confronting inequality and corruption in the European political arena, with a power base in the indignidados youth movement. Their Middle Eastern and North African counterparts, however, failed to live up to their desires of a free, democratic and equal society in their respective countries.

Tunisian exceptionalism?

Despite the chaos reigning in neighboring Libya, Tunisia came out of the quagmire intact. The small North African country remained a beacon of light, proving to the international community that democracy is more than just a myth in the Arab world, while undermining the axiom that Israel is the only democracy in the region.

Tunisia also remains the great hope for left-wing anti-globalization movements. During the 2015 World Social Forum, which was held in Tunis, an Argentinian social activist spoke about the role of left-wing social movements in the 21st century, stressing that Latin Americans consider Tunisia the only place in the region where the Left is still alive and kicking — where it is trying to preserve ideals of social equality and workers’ rights.

In December 2015, Tunisian Union Général des Travailleurs Tunisiens (Tunisian Labor Union), the oldest labor union in the Arab world, won the Nobel Peace Prize, which it shared with Tunisian Employers’ Association, UTICA, the Tunisian Bar Association, and the Tunisian League for Human Rights. The prize came following two years of incessant work to ensure national dialogue between the divided parties, following the assassination of Chokri Belaid and Mohamed Brahmi, two leftist political figures, in 2013.

The jihadist temptation

The youth of the region are caught between the hammer of long-term unemployment and the anvil of ISIS’ temptation. The International Labor Organization place the Middle East and North Africa in the category of highest unemployment rate in 2014, with a 40 percent rate in Tunisia among youth, and 60 percent for young graduates. These alarming figures vis-a-vis the only successful story of democratic transition in the region hides serious dysfunctions in the system, reflecting a deep malaise among young people who are trying to live a decent life.

Since appearing in Syria following Assad’s bloody repression of the Syrian revolution, ISIS has marketed itself as an alternative to the status quo of political regimes in the Arab Spring countries. For many young people in the region, jihadism was simply too tempting to miss out on.

There is a common notion according to which young people in the region are de-politcized. Yet their apathy is compounded with a deep sense of skepticism of political class elite — an archaic grou[ that is disconnected from the issues most pressing for young people — sometimes to the point that it views their constant calls for change with disdain. The establishment will not let go of the privileges it won through elections, in which they promised the people change, yet never kept those promises. Young Arabs who felt disenchanted took to the streets of Kasserine, Sidi Bouzid, Cairo on both January 14 and 25 — dates that had come to symbolize the Tunisian and Egyptian revolutions, respectively.

The lack of economic opportunities, political marginalization, and a struggling civil society trying to keep up with aspirations of the Arab Spring youth — in the face of state-sanctioned violence against them — are indicative of what some political analysts nicknamed the “Arab Spring disease.”

There is still hope in sustaining youth civic participation amid the tense atmosphere. But there needs to be a re-definition of leadership, away from the indoctrination of the old elite while highlighting civic participation as a means to counter radicalization.

In the meantime, young people in Kasserine, Cairo, Tripoli, Sanaa, and other places where the 2011 uprisings changed the face of the region continue their struggle for a better life, while challenging the grip of authoritarianism and terrorism.

Houda Mzioudet is a Tunisian journalist. This article was first published in Hebrew on Local Call. Read it here.