Although goldsmithing among the Jewish community in Yemen goes back generations, most Yemenites were stripped of their ability to continue their work upon their arrival in Israel. The few who remained in the profession watched as their work lost its meaning in Israeli-tzabar culture.

By Tom Fogel

My family from my mother’s side is a family of goldsmiths. It’s a bit strange to write that out, since none of the grandchildren bore witness to our family’s profession. Like many who came from Yemen, the patriarchs of the family were not allowed to bring their tools to Israel, and the women’s jewelry was buried in the sands of Aden. And those who did bring their tools and jewelry did not get them back upon stepping off the plane. Many Yemenite immigrants say the lack of those tools led to their desperate situation upon arriving in Israel. They were used to the social mobility that accompanied a profession such as goldsmithing. In Israel, in the ma’abarot (transit camps for Jewish immigrants) and afterward in permanent towns, they were pushed into working in agriculture and construction. Many weren’t able to break from the route planned for them, and never returned to goldsmithing.

A new book by Yael Gilat brings the stories of Jewish goldsmiths who were able to break through this barrier and continue their work in Israel. Some of them insisted or lied in order to bring their tools along with them, while others were integrated into hegemonic institutions that allows them to work in goldsmithing. But whether they were independent or employed, these goldsmiths were resigned to adapt to the reality and fit themselves into the way the hegemony views them on the one hand, and the way it views their jewelry on the other hand. Their personal stories tell the history of Yemenite art as it encounters Israel’s hegemony.

Mizrahi authenticity, Hebrew antiquity

In the beginning of the 20th century, the study of Eastern culture sought to locate the ancient and untainted source for contemporary Mizrahi culture, which is seen as inferior. Zionism and Israeliness sought the Bible in the Middle East, specifically in Yemen. The biblical branding had two functions: it allowed a burgeoning Israeli-tzabar culture to adopt Mizrahi motifs (folk dancing and music, embroidery) while granting Arab-looking Jews who spoke Arabic, as guardianship of an ancient biblical culture.

Yemenite singer and dancer Lea Avraham:

The attitude toward the cultural material assets brought by the craftsmen and women was different from than other identity attributes such as language, music, storytelling and tradition. Gold crafting, dress and embroidery were appropriated for the benefit of a renewed national identity. Part of this appropriation took place when the jewelry or clothing in question was stripped of the meaning given to it in Yemenite society, and was connected to an “ancient Hebrew” tradition. Thus, it lost its symbolic connection to the culture which created it. Although the hegemony recognized jewelry and embroidery as part of a higher culture, it also emphasized the need to “save” the crafts from their creators, thus redeeming the primitive artists. In other words, embroidered pants belonging to a Yemenite woman is a sign of primitivity.

Artists or ‘the artists?’

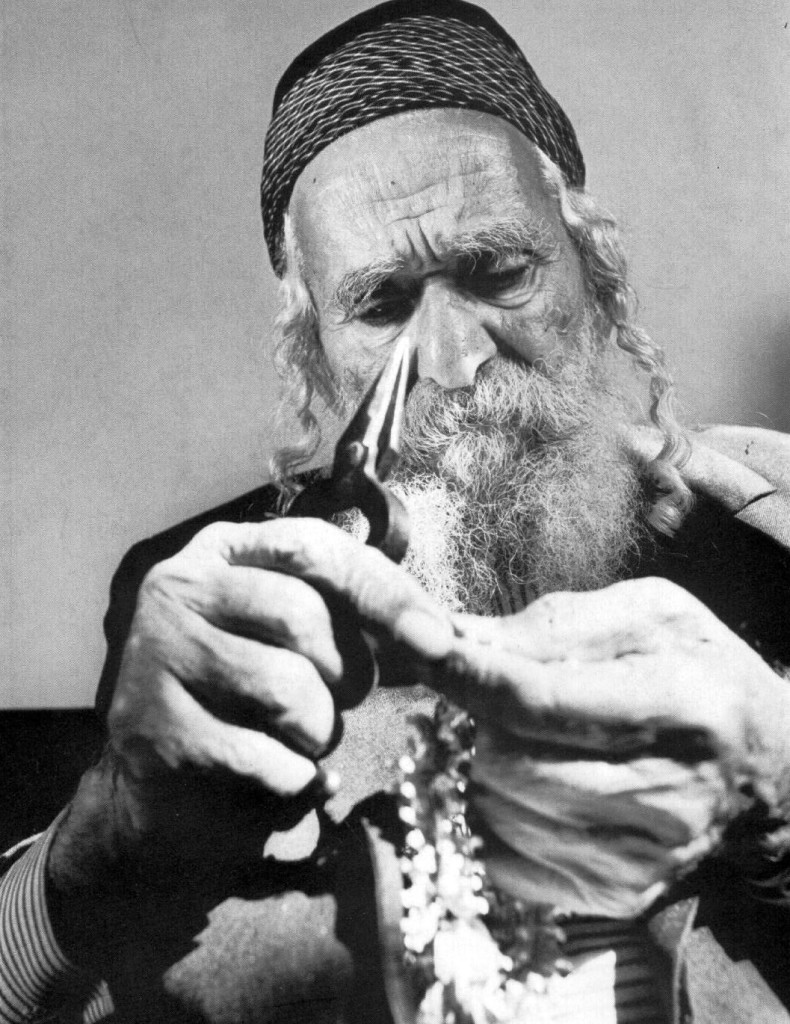

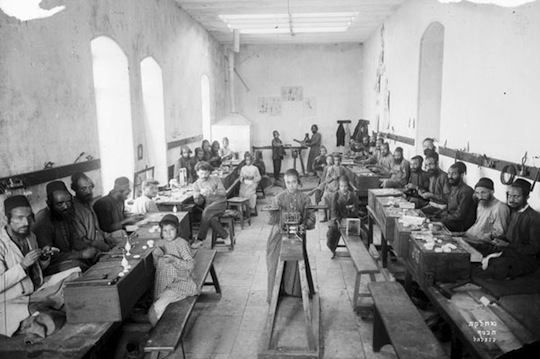

The first institution that established ties (and an exploitative relationship) between Hebrew art and Yemenites was, of course, the Bezalel Academy of Art and Design. Elderly Yemenites would model during drawing classes – portraits of the fathers of a nation. At the same time, Yemenite artists were sitting in an adjacent room and creating replicas under the tutelage of Bezalel instructors (headed by Boris Shatz), with no recognition of credit for the final product. The European designers were the artists, while the Yemenite goldsmiths were just artists.

Ruth Dayan’s Maskit was another institution that was established later on. Maskit provided work for jewelers and embroiderers who used traditional techniques for European designs. There, jewelers from the Hidan district (the David and Ben-David families) stood out. The goldsmiths adjusted to using what they called “shortcuts,” meaning that they isolated one motif from a large piece of jewelry, so that it matched the taste of the Israeli market. Even goldsmiths who worked independently found a way to take a “shortcut” and make Yemenite jewelry appealing to the non-Yemenite audience. The audience’s taste also turned Muslim jewelry, which was worn exclusively by Muslims in Yemen, to that which represents ancient Hebrew culture.

It is interesting to note that due to the internalization of the Western gaze, some goldsmiths hold on dearly to the worth of handiwork. With the changes that the jewelry (and its target audience) has undergone, handicrafts have remained a hallmark of Yemenite culture. Handcrafting did not have an intrinsic value in Yemen – it was part of reality. When the Turks brought machines to Yemen, the goldsmiths used them to the point that they forgot some of the traditional methods of gold crafting. This teaches us that changes also took place in the East, contrary to the worldview that sees the East as a place frozen in time. In any case, a good portion of the Yemenite goldsmiths’ symbolic capital rests on the fact that precise handcrafting and the prices of handmade jewelry is very expensive. Many Yemenite goldsmiths dedicate a section of their workshops to traditional jewelry, although it seems that its place is more symbolic, rather than economic. Its presence in the workshop space constantly confirms and renews the connection between tradition (which is always present) and the always-changing present.

Speaking of cultural capital, today when sellers in the jewelry market in Sana’a try to get the attention of potential customers, they use the phrase “Jewish handiwork.” Today, the word “Jewish” in Yemen’s jewelry market has similar connotations to the word “Yemenite” in Israel.

Several years ago I experienced a defining moment in a museum in the Eretz Israel Museum, which exhibited a “Leba,” an intricate Yemenite necklace. I thought about my mom and how much she loves and appreciates this kind of jewelry, and that she has none of her own. On the one hand I hear many stories about jewelry and goldsmiths, while on the other hand my family has nothing concrete left.

I was lucky to study goldsmithing under Ronen Sharabi from Rehovot, a virtuoso of the filigree technique. Alongside the desire to create, spending time in his studio allows me to re-acquire my family’s profession. Thus, my first piece of Yemenite jewelry was given to my mother, Shoshana.