A new report by B’Tselem concludes that the Israeli military’s investigations into its own alleged crimes are little more than a whitewash. So what comes next?

Sometimes a seemingly dry bit of research can seem to rise to the level of literature, challenging the status quo in ways that, in the long run, only literature can. Take, for example, the first Arab Human Development Report. Penned by researchers from the region, the 2002 report concludes, rather boldly, that “the predominant characteristic of the current Arab reality seems to be the existence of deeply rooted shortcomings in the Arab institutional structure.”

Sure, that conclusion was used in too many reductionist opinion columns following 9/11. See, for example, Thomas Friedman’s 2002 piece, “Arabs at the Crossroads,” in which he declares that to “understand the milieu that produced bin Ladenism,” one need only “read this report.” But for the vast majority of Arabs who grew up in that milieu (myself included) and did not embrace “bin Ladenism,” Friedman’s invitation was neither here nor there. If we studied the report, we did so because it concerned us, because we weren’t afraid to see our notions of ourselves refracted, even reversed.

This mirroring is precisely what good literature can do. But to do so, it must not shy away from its cause. And that, I fear, is what discerning readers might conclude about a new report by the consistently top-notch Israeli human rights group B’Tselem.

Earlier this week, I sat down to read “Whitewash Protocol,” the organization’s latest report which offers a review of the Israeli military’s investigation of alleged abuses and crimes during Operation Protective Edge, the 2014 “round of fighting” (the quotation marks are B’Tselem’s) that left 68 Israelis and 2,202 Palestinians—546 of them under the age of 18—dead.

Here’s an excerpt from the introduction:

This paper … aims to review how Israel chose to investigate suspected breaches of IHL [International Humanitarian Law] that took place during Operation Protective Edge. The repeated pattern of whitewashing, as described in [a previous B’Tselem report on the matter, s.b.], formed the basis for our decision to stop referring complaints to the military law enforcement system. However, as any system is capable of self-correction—at least in theory—we decided to examine, two years after the fighting ended, how the military law enforcement system has performed.

Fair enough, but the report is bookended by two seemingly contradictory statements: First, that it sets out to test a theory (that “any system is capable of self-correction”); and, second, that the subject at hand far too grave to be looked at as “a theoretical issue.”

Here are the last lines from the report:

There was no accountability after Operation Cast Lead, only whitewashing. Now, after Operation Protective Edge, there is no accountability either, only whitewashing. This is not a theoretical legal issue: we are talking about human lives, and the toll might, heaven forbid, mount even higher.

So why posit a theory—and spend 13,000 words testing it—only to conclude by warning off theoretical pursuits altogether? The question is even more perplexing when one considers that B’Tselem and others have, since 2014, issued several other reports essentially disproving the theory that Israel’s military “justice” system could self-correct. Just weeks after the fighting ended, B’Tselem Executive Director Hagai El-Ad himself said: “Common sense has it that a body cannot investigate itself.”

Perhaps with this latest report, B’Tselem is trying to keep a step ahead of Israel’s Military Advocate General (MAG), to whom it has refused to hand over details on alleged Israeli abuses in Gaza — the better to not abet its whitewashing. In that case, it makes sense that the organization continue to shine light on the MAG’s updates on its investigations into “exceptional incidents” during Protective Edge, including a June update that cleared the military of wrongdoing in the July 16, 2014 attack that killed four children from the Bakr family as they played on the Gaza beach:

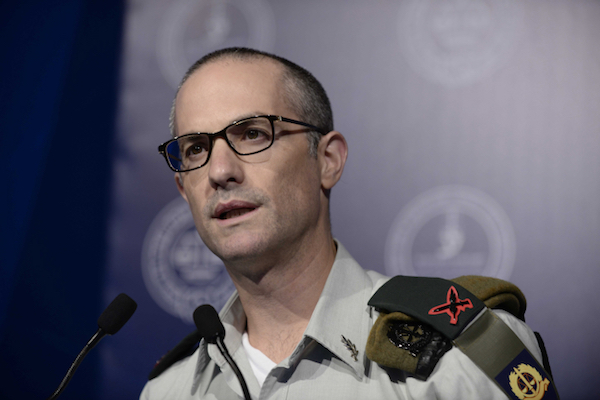

Israel’s interest is to stave off an investigation by the International Criminal Court (ICC). To illustrate the point, B’Tselem cites in its report former MAG Major General Danny Efroni, who warned: “If the probe is a whitewash and not a true investigation, nothing will stop the ICC.” So calling the MAG’s investigations just that — part of a “whitewash protocol” — is compelling, from a legal perspective. But remember that last line: “[t]his is not a theoretical legal issue; we are talking about human lives…”

I can get behind that, especially after seeing those human lives up close. But the circle I can’t seem to square is this: How many more times can people — or, indeed, organizations — of conscience investigate a system that refuses to honestly investigate itself? If speaking truth to power has done little to advance that truth, might the powerless embrace another truth?

That question takes on more urgency for those closest to the struggle. There can be no equivalence, of course, between what an Israeli must consider and what a Palestinian, stripped of choice by the Israeli occupation, must endure, but I nonetheless read with interest my colleague Mairav Zonszein’s recent piece in The Forward, in which she asks: “Should I give up on changing Israel from within — and take a stand by leaving?”.

As a Palestinian, I must accept that my opinion on the question may never be an empathic one. But I don’t doubt Mairav’s intentions. So, too, with B’Tselem. I admire the perseverance, the “optimism of the will,” that compelled the organization to produce another finely researched report on the ever-deeper entrenchment of the system it seeks to change. But in its final words — where B’Tselem concludes that, “what we said then still holds true now, and that Israel continues to devote most of its efforts to creating a façade and nothing more” — I am left wondering what comes next.

To read “Whitewash Protocol” as literature is to be left aching for a denouement, some resolution — some way forward — for its protagonists. None of this is to say that B’Tselem and other human rights organizations haven’t done a fine job within their mandate. They have. But as it stands, this latest report tells us what we already know (thanks to B’Tselem itself). It presses the fret just a little longer, extending the solemn note of our inability — all of us — to force a reckoning for the wronged.

I can’t presume to know what B’Tselem’s alternatives might be — or the costs of choosing them. But I do know this: I’m tired of the same old story. I want to know how this one ends.